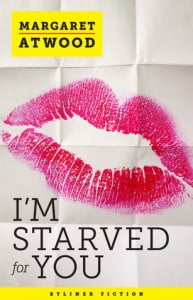

Reviewed in this essay: I’m Starved for You , by Margaret Atwood. Byliner, 2012.

, by Margaret Atwood. Byliner, 2012.

Margaret Atwood’s latest dystopia trades The Handmaid’s Tale’s theocratic republic and Oryx and Crake’s bioengineered wasteland for more familiar locales. Set in the gated community of Consilience, a think tank-generated portmanteau of “cons” and “resilience,” the mordantly funny I’m Starved for You (an e-book exclusive release that the author calls a “long/short story”) imagines a discomfortingly near future where a generalized economic collapse and staggering unemployment give rise to volunteer prison sentences.

Individuals and even couples sign up for an alternating series of month-long terms in Positron, more a self-sustaining economy than a penitentiary, and when their month is up, they’re put to work in métiers as diverse as poultry farming and prison security. What’s more, they swap their orange jump suits for their “civvies” and ride their Consilience-issued scooters to the fully paid house they exchange, in the off-season, with their never-to-be seen Alternates. Everyone marvels at the convenience of the arrangement, and few seem to mind trading off their civil liberties, provided all’s looked after behind bars. Open dissenters are scarce, maybe because troublemakers tend to disappear. Proper criminals also take turns in and out of Positron, we learn, at least until their baser instincts kick in and the authorities are called to restore order. Where the agitators go from there is anybody’s guess, and nobody’s guessing as long as the food’s good.

Atwood’s greatest strength as a writer of speculative fiction has always been her knack for delivering worst case scenarios with devilish pragmatism – her own distinctively terse voice slipping imperceptibly into the legalese of her created world. Here, too, monstrous daily routines are recounted with deadpan precision, and moral blips registered without comment. When one character lets her mind coolly wander to the possibility of killing someone, she’s fixated on the details: disposing of him would surely call for a body bag, she thinks, and how might one lug such a thing around without being noticed? Insofar as the story makes an argument, it’s that Orwellian solutions to complex socio-political problems – the recently passed omnibus crime bill seems an obvious reference point – breed such banal forms of evil.

Tidy as this introduction to Consilience is, it doesn’t preclude Atwood from addressing the messier underside of the experiment, namely the sexual appetites that Positron’s Bing Crosby-scored walls can’t quite contain. The story hinges on the accidental crossing of a pair of Alternates via a wayward note that’s capped with the titular send-off and sealed with a gaudy purple kiss. The sender’s identity is easy enough to guess, but Atwood smartly plays up the arbitrariness of the mystery, showing how this world’s stultifying routines turn even desire and personal identity into moot points. In recent work like The Penelopiad, Atwood has largely turned away from round characters to the broad strokes of her drawings, with mixed results. Here that approach is exactly right: why personalize your civvies when you’re bound for orange anyway?